My old friend Dr. Mark Renneker was in town last week and, rabid film fanatic that he is, he literally dragged me to go see something called Storm Surfers 3D. Relieved that it didn’t sound the sort of vulgar slasher flick he normally patronizes at midnight in the seedier districts of the San Francisco Bay area, I dutifully followed him to the late show, which in Lihue, Kauai was of course attended by about 3 surfers and 43 chickens that wandered in through the open exit to scarf up the groundball popcorn left by the 7:45 show.

As it turned out, Storm Surfers 3D followed the duo of my old pro tour mates Tom Carroll and Ross Clarke-Jones as they took up the White Man’s Burden and quested the Seven Seas for enormous mutant waves that seem to be an idee fixe for retired pro surfers, waves that are sort of a cross between the Elephant Man and Godzilla but with the temperament of David Berkowitz. The only reaction the film had upon me was to induce an overwhelming fatigue – not because the film was not exciting (it certainly was) but because there were numerous establishing shots of our heroes bundled up in 16 bolts of Quiksilver swag well before dawn on some desolate beach halfway around the world, and all I could think was You really got up at 3:42 AM just to get waterboarded by the kind of rogue wave that compelled Leslie Neilson to utter “Oh – my- God!” in 1972’s The Poseidon Adventure?

The amount of gear necessary to mount these expeditions quite literally filled a warehouse and I suffered empathic exhaustion much like an insomniac counting sheep, agonizing over all the schlepping necessary to transship all the jet skis and rescue sleds and oxygen canisters and Michelin Man wetties across the planet. I found myself whispering to Renneker, “Every time the balloon goes up and that surf forecaster sends these guys off on another Pin-The-Tail-On-The-Donkey joust against a tsunami, it’s another 100 grand.”

As for the merits of the film itself I will state only that had Werner Herzog directed it, it would have been the best picture ever made about surfing. Herzog might have entitled it A Farewell To Arms and wrestled from the shamelessly commercial enterprise a statement on manhood that would have induced Hemingway to chuck his double-bore Holland and Holland in the woodpile and buy a Yamaha 4-stroke and impact vest.

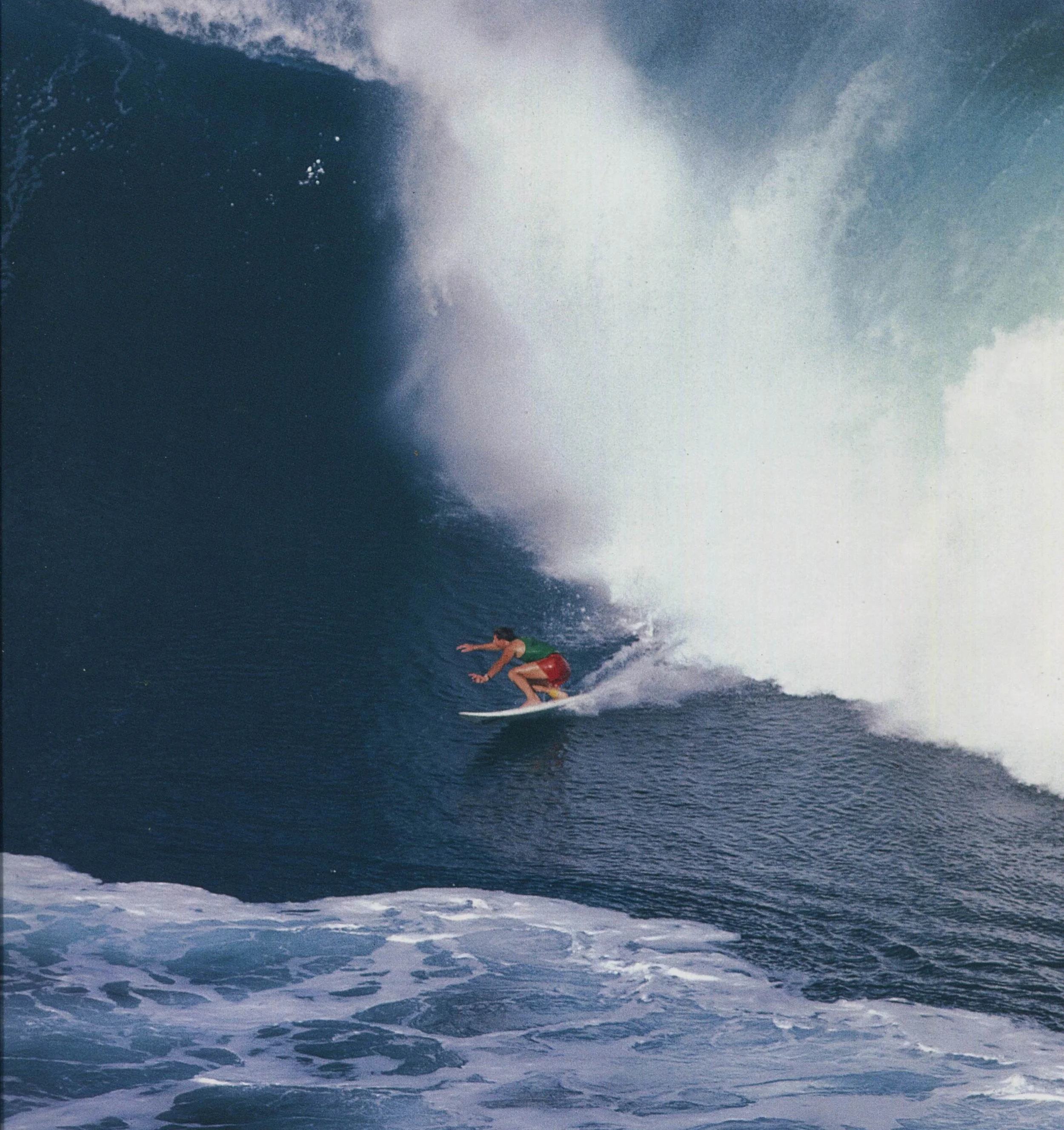

Yet this is all by the way. The experience of seeing Storm Surfers 3D was noteworthy to me because it reminded me that back in 1986 I happened to be sitting out in the channel at Waimea Bay at the very moment Ross Clarke-Jones climbed into the big-wave pantheon. This was during the ASP Billabong contest, green-lighted on a December day when 30-foot close-out sets had impelled the event directors to nearly cancel the event that morning. Having arrived late to the beach – not that I would have ever considered having a ‘warm-up surf’ at the Bay on a close-out day – the first sight that greeted me was a set fringing across the entire bay, followed by my mate Robbie Bain frantically scouring the contestant gallery for someone to caddy him in the first heat. I immediately raised my hand, thinking that since I’d be sitting on the beach all morning waiting for my later heat, the best way to get a grip on things would be to get out the back and spoor that wooly old mastodon in its lair. Bainy reckoned that I could also caddy for Ross. As it seemed unlikely that both of them would get in trouble, I flippantly shrugged my assent, tied two leashes together and attached the resultant Gordian Knot of urethane to my borrowed Willis Bros. 9’6” single-fin (an hour earlier it had been half buried in red mud beneath Michael Willis’s house), and followed the boys out through the somewhat agitated keyhole on the north end of the bay and headed out to the lineup. A Brazilian bloke and four-time World Surfing Champion Mark Richards rounded out the four-man heat. Luke Egan was caddying for MR, so we settled into a cozy little spot athwart the 20-foot lineup and watched the ginormous (I was going to say ‘beastly, grunting’ but figured I would owe Nick Carroll a royalty) waves hammering the reef, beholding them with all the stilted joie de vivre of two young men who weren’t exactly sure whether they might be called into combat or were merely observing the artillery barrage from a forward post.

It was a beautiful day. The sea was smooth and cobalt blue. A gentle offshore breeze wafted out of the Waimea Valley smelling of plumeria. The lava point shuddered and throbbed like an enormous boom box with the detonation of each wave. The waves, Luke and I estimated, were about 85 feet.

The horn bleated and general-issue Contest Surfing, Normal ensued, the four surfers trading moderate-sized sets and looking as if they were actually enjoying themselves.

Then the seaward horizon disappeared. A cacophony of screeching spectators and howling car horns rose in a crescendo from the amphitheater formed by the beach and Kamehameha Highway flanking the bay. Water Patrolman “Squiddy” Sanchez came flying past Luke and I on a jet ski, yelling “Get the hell out of here!” And then there it was, marching in from the west, the fabled nightmare I’d read about in surfing magazines since I was a boy – a close-out set at Waimea! The entire mouth of the bay appeared to suddenly be boxed in by a mobile, tottering blue-black canyon wall.

I turned to Luke and bellowed, “Paddle for Haleiwa!”

The first wave of the set was a 30-footer. Luke and I barely made it over this one and were lost in the nearly black curtain of its spray as it reared up and went Ka-WHUMP! across the bay from point to point. Desperately trying to peer through this impenetrable mist as we scrambling seaward, we froze in horror as another even bigger wave materialized before us. Somehow Luke and I managed to make it over this one, too, and I remember the rollercoaster-drop tickle in my gut as we crested the fringing monster and dropped down its back.

At this point the only other surfer in the lineup was Mark Richards. He’d made it over the first couple of dumpers with us. Bainy and the Brazilian weren’t so fortunate. They had been keelhauled all the way to the sand and Bainy, a big fan of the Marbs, had nearly drowned. They were done. Ross Clark-Jones however had been inside after a ride and was gamely struggling back out toward the lineup. But that was a few minutes away.

Now, out the back, the offshore sea spray melted away to reveal Mark Richards in sole possession of the line-up at Waimea Bay facing the biggest rideable wave in a surfing competition since the 1974 Smirnoff Classic.

This wave came marching in on the heels of the close-out set, massive and staggering as its boots began to drag on the reef, stunningly beautiful with a creamy turquoise glow churned into it by the effervescence wrought by the explosive close-out set. As it stood up in front of MR, Luke and I from our loge seats in the channel could clearly see the expression on his face. It was one of resolve. It was the classic Aussie Digger gene in full play. He didn’t like the looks of this wave, but goddam it he was going over the barbed wire straight at the machine gun nest.

When the wave crested Mark Richards sat up in his stirrups and wheeled his gun around and – just before he took his first pull – I clearly saw his eyes widen and his Adam’s Apple bounce in his throat. Car horns were blaring through the uproar of hooting spectators. Then the wave vaulted into an enormous green-blue cathedral as MR snapped to his feet and plummeted in free fall toward the trough. The barrel was enormous and terrifying to behold at close range, and ribbed with a series of side waves pulsing through it at right angles to the face – these were shock waves from the lips of the preceding close-out waves, lips that had detonated in the middle of the Bay just seconds before. MR made it to the bottom and unfolded into one of his classic knock-kneed bottom turns, the same sort of turn that had won him acclaim during his very first surf ever at Waimea, at age 17, in the 1974 Smirnoff Classic.

As MR disappeared from our view, next we watched Ross Clarke-Jones battle his way into the line-up and snag a similar Waimea gem, and the expression on his face said that he’d found his true calling, that after seasons of suffering in small slop on the circuit this was more like it. He went on the attack and by the time he stepped onto the sand at the end of the heat his reputation as a big wave charger was already being relayed on the coconut wireless.

Such was the North Shore of Oahu in the days before jet skis and towropes and prizes paid out like bounties on coyote pelts. Reputations born or enlarged; and reputations torn in shame (a number of ASP Top Sixteen pros were handed the White Feather when they withdrew from their heats on this day). For me however, an eyewitness at close range, while it was noteworthy to observe the very wave that began Ross Clarke-Jones’s career as a big wave surfer, my old fashioned tastes keep me coming back to Mark Richards and his tussle with the wave he later called ‘my biggest ever.’ You see, Richards later admitted that when facing that wave alone in the line-up he had known fear, but that he realized every single person of note in the international and North Shore surfing scene was clustered in the ultimate peanut gallery on the beach and cliffs. Like a gladiator at the very pit of the Coliseum, he was considering those thumbs-ups or thumbs-down verdicts. That was the mettle and make-up of the men from the Free Ride generation whom I followed into battle on the pro circuit. No skis, sleds, Mae West vests, Spare Air cylinders, and support teams. Just one man out the back in front of the entire surfing world facing the biggest wave he’d ever encountered. Not resting on the past laurels of four world titles. At nearly 30 years of age still determined to prove himself in surfing’s most fabled arena. That to me is a thousand times more heroic and dramatic than anything at Cortez Banks or Shipstern’s or wherever surfers grab the towrope.

I’ll never forget seeing Mark swallow his fear with a gulp visible from the channel before he sailed over the ledge on the biggest wave he would ever ride.

MR Would Go…..